I recently bought myself a Polaroid rollfilm camera that had been converted to take packfilm. Several services started doing this modification after the final Polaroid rollfilms (Type 42 and 47) went out of production in 1992; the most prominent modders were a company, now gone, called FourDesigns. The conversion required some cutting and machining of the camera back, plus the removal of its internal roller plate, which had the advantage of making a heavy camera noticeably lighter. It was expensive, so most were conversions of only the high-end Pathfinder series, a.k.a. Model 110, 110a, and 110b, sold from 1952 to 1964. Mine is a hybrid, with a 110 front end and a 110a rangefinder/viewfinder on top.

Now that packfilm is on the extinction list, those old conversions are about to get less useful. But I bought this camera for a reason: I recently discovered that Instant Options, a camera-modification business run by a guy named Nate in Florida, converts Pathfinder cameras to take Instax Wide film. (I have read that he’s effectively the successor to FourDesigns, having acquired their stock of parts after they closed down.) That interested me greatly, because Instax Wide film is readily available and fairly cheap, and seems likely be in production for quite some time to come. (Fuji introduced a new Instax Wide camera this year, strongly suggesting that the film’s here to stay indefinitely.) The Instant Options conversion from an unmodified Pathfinder camera is expensive, but if your camera has already had a packfilm back installed, it’s a lot less: He charges $175 plus shipping. I sent mine off to have it converted, as a Christmas present to myself, and got it back a few days ago. I’ve been shooting with it since then, and I am delighted.

Here’s a pair of views where you can see the modified back.

Now, do not misunderstand me: There are drawbacks to this thing. A Polaroid rollfilm camera is a bulky, awkward object, awkward in the hand. My brother-in-law saw me shooting with it, and said, “It’s like you’re coming at them with a toaster.” The Instax back makes it even more awkward, because you have to crank-eject the picture while holding a release switch. You can’t shoot with it very quickly. You also can’t really use it on a tripod, because the hand crank bumps into the mount, so you’d have to remove the camera from the tripod to process each photo. But there is most definitely an upside, and it’s this. Instax film is superb, but Instax cameras have mediocre lenses. The Pathfinder, by contrast, has a premium f/4.5 lens, made by Wollensak, with full manual settings and a fine mechanical shutter. In other words, you’re taking film that is never really used to its full potential and putting it behind much better optics than you’d otherwise get.

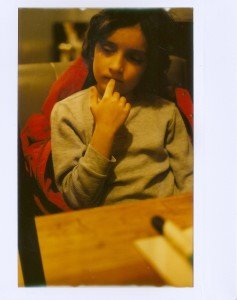

The resolution and crispness of the couple of dozen pictures I have taken this week astonish me. Take a look at this one. (No flash, using available light in a restaurant. Instax film is rated ISO 800, nice and fast.)

Now look at this closeup of the waffle-weave shirt. (Please ignore the lint, which is there because I didn’t clean the scanner glass.

It has none of that plastic-lens muckiness that you get with point-and-shoot cameras. That picture is sharp.

I could not be happier with Nate’s handiwork–the job he does is quite neat and refined–and I have been toting this absurd object around throughout the holidays and every day this week. (In case you were wondering: I paid full fare, and this post is not any kind of discount-wrangling or payback or anything nefarious like that. Enthusiasm is my only motivation here.) He will hot-rod your camera with bright-purple leather or whatever other pizazz you desire for a small upgrade fee. I stuck with the standard dark-gray Polaroid covering, because I am a dark-gray kinda guy.

Highly, highly recommended: Click here to get your own conversion done. I plan to rig up a shoulder strap soon–probably dark gray–so I can shoot with mine more easily on the New York streets come summer.

Two test frames of New55 Color. The white is pretty white, the red and blue and yellow are decently saturated, and the definition on the brass trumpet is fine. A very strong prototype. (Click through twice to enlarge.)

Polaroidland visitors almost certainly know about New55 by now. Bob Crowley’s Massachusetts startup, just a short drive from Edwin Land’s vanished Cambridge mothership, got started with a Kickstarter campaign to make single-shot black-and-white instant film, akin to (and in some ways improving upon) Polaroid’s old Type 55. Despite some significant production problems at the beginning, New55 has been making and selling a solid and usable peel-apart product, improving it along the way. Given that black-and-white Type 100 film was my single favorite instant-photography product, I have been very, very pleased to see something like it return to the world.

Amazingly, Crowley and his team have not been worn out by the bumpy ride they’ve had so far, and last week opened a second Kickstarter campaign, for a color New55 film. Color, of course, brings extra complexity, and requires new chemistry, but more than that, New55 needs modern machinery to get into this game in a big way. Its development pods are made on an old Polaroid machine that gets balky and requires adjustment between runs; the reagant is made with legacy equipment as well. A ridiculous-looking (though quite sophisticated) homebrew machine has done a lot of the coating.

The Kickstarter goal is $400,000. We’re about a week in, and about $60,000 has been pledged: good news, but not good enough yet. If you care even casually about the future of instant film, this is something you need to get behind. (Disclosure: I am contributing some signed copies of my book as Kickstarter rewards, and also backing the project with a pledge of my own.)

Nobody wants to oversell this based on future products that may or may not happen: New55’s aim right now is to make single-sheet instant film, to be used in 4×5 view cameras. However, if you are one of the many, many photographers who are unhappy about the end of Fuji’s FP-100C Polaroid-compatible packfilm, this campaign is important. The New55 folks, bolstered by some enthusiasm and publicity from Florian (Doc) Kaps and his new company Supersense (“home of analog delicacies”), are pretty clearly thinking of this as a test for the future production of film packs. Such a product line is a long way off, to be sure, but if the single-sheet version does not get off the ground—allowing for refinement, field testing, and development on a modest scale, to justify investment in the huge build-out required to make ten-shot packs—there is very little chance that we’re ever going to see a Type 100 product again. This is a way to preorder some film and also a way to make your enthusiasm known. Send ’em some money.

UPDATE, December 2016: Sad news. Kickstarter campaign did not meet its goals, and development of new color peel-apart will most likely not go forward, unless some other entity picks up the torch.

Hello! To anyone who’s still listening.

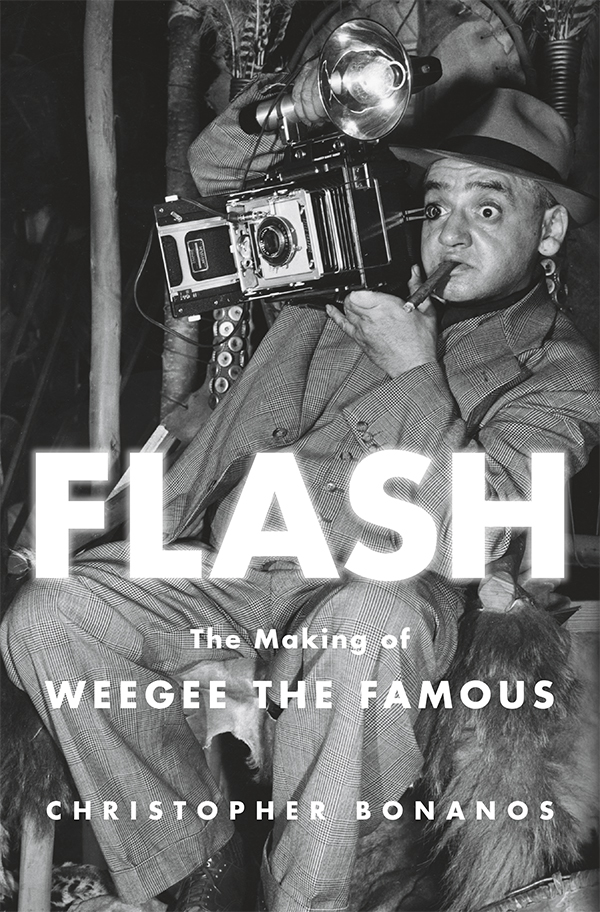

I have gone silent on Polaroidland these past few months because (a) I’m burrowed deep into the next book, and (b) this Website has had technical problems stemming from a malware infection, and has been intermittently shut down for scrubbing. Problem (b) has been straightened out, and we’re back up for the duration. As for point (a)—well, the manuscript’s supposed to be done this spring, and I hope to hell it’s any good.

It has been one bummer after another lately for instant-photography enthusiasts—at least, until this week brought some happier news. Earlier this year, Fujifilm announced its decision to shut down production of FP-100C, its last peel-apart instant film. Millions of cameras that take Type 100 film are now on borrowed time. That also left only New55 making any kind of peel-apart product, the early production of which ran into difficulties owing to a bad coating job by a supplier. And the 20×24 Studio has also announced that it will, most likely, make its final photographs in 2017. It sounded, for a few weeks there, like we were down to Instax and Impossible films, and that would be that.

However, this week brought quite a turn. New55 has announced that it will be Kickstarting a program to expand its production and begin making color instant film. If that fundraising effort is successful, it will serve as a proof-of-concept toward the production of packfilm. That’s right: small-scale enthusiast production of Type 100 film. For that, New55’s Bob Crowley will be working with none other than Florian “Doc” Kaps, co-founder of the Impossible Project. In other words, the only people outside Fuji/Polaroid/Kodak (and, I guess, the Soviet Union) who’ve ever manufactured instant film are pairing up to start a peel-apart line. I can’t believe they’re doing it; I also do believe that they can.

The Polaroid Swinger was introduced to the world in July 1965, and two recent newspaper stories marked the anniversary in fine form. One is from the Boston Globe, written by your Polaroidland host. It’s visible here, on BetaBoston, and (I’m told; haven’t seen it yet) it’s running in the business section of today’s print edition. Analog printing, baby! Nothing like it.

The Polaroid Swinger was introduced to the world in July 1965, and two recent newspaper stories marked the anniversary in fine form. One is from the Boston Globe, written by your Polaroidland host. It’s visible here, on BetaBoston, and (I’m told; haven’t seen it yet) it’s running in the business section of today’s print edition. Analog printing, baby! Nothing like it.

And about two weeks back, the New York Times ran a similarly nice post about the Swinger that draws heavily on, and name-checks, INSTANT. This one’s by the presidential biographer and historian Michael Beschloss, apparently taking a break from FDR and JFK to slum it with Dr. Land and me. I am delighted.

It’s almost alive! Still! And it would be, if only someone could make some Type 20 film.

A sad day here in Polaroidland: Bill Warriner died early this morning in Tucson, where he lived with his wife, Cheryl Cooper. He’d had heart trouble in the past year or so, helped but not entirely fixed by surgery, and (when last we e-mailed, a few weeks ago) was upbeat but realistic about his prospects.

In fact, upbeat just begins to describe Bill. I met him, electronically, in 2011, when I was still at work on the Polaroid book, and our encounter was unintentional. A group of Polaroid alumni and retirees, Bill among them, had been discussing a few pages from the book’s galley proofs on a long e-mail chain. Most of the commentary was along the lines of “sounds promising.” In among those one-line remarks, though, was a vast amount of commentary from Bill. It was thoughtful and incredibly enthusiastic, to the effect of “I don’t know this guy, but it sounds like he got it! This is the book we all wanted someone to do!” When I got in touch with him myself, he was no less bubbly, and his enthusiasm carried through publication and then some.

It may have been that, because he was a maker of films and pictures and books himself, that he understood the deep trough one goes into, mentally speaking, late in a project like this. Toward the end of a long push, when you’re verging on revulsion for your own work and your energy is not just flagging but drained, there is nothing like a few words from someone who knows what he’s talking about. Bill offered more than a few, for which I will forever be grateful. When I asked an old colleague of his about that, he chuckled and said, “Bill is always excited.” He was, it seems, an exceptionally positive soul.

And, my God, an erudite one. His résumé is a type you don’t see much anymore: the Air Force, a stint in Korea just after the war, studies at Yale’s Institute of Far Eastern Languages and later at Harvard, and then audiovisual projects everywhere, especially for IBM and, of course, Polaroid. Ask him about filmmaking, and he’d toss off a funny yarn about cutting negatives in a Fifth Avenue office in the sixties. Ask him about a translation of your book, and he’d explain how the three syllables “pol-a-roid” went into Mandarin as “pai-li-de,” more or less. He could still sing Tom Lehrer’s custom-written Polaroid version of “The Elements” from memory 40 years after it was commissioned, and even led me to Mr. Lehrer himself. In between the learned messages came the smart goofy ones: e-mailed jokes, silly pictures, funny political observations, random screenshots of beautiful science and the Arizona xeriscape. (A couple of weeks ago, he posted this link on his Facebook page.) He had interesting, informed things to say about coffee and geology and a lot of other things. And about Cheryl, whom (it was very clear, even from here) he adored.

As I’ve discussed on this site, Bill in 1970 made a short film of Edwin Land called “The Long Walk,” in which Land laid out his vision for the future of photography and seems to predict our contemporary smartphone world with uncanny precision. I’d seen the film on a transfer from videotape, and that was good enough to write about what it contained, but the day after INSTANT was published, a 16-mm. print turned up, uncannily, on eBay. Even more uncannily, I brought it home for not very much money. (You can watch an HD copy of that print on YouTube here.) When I posted the film online, Bill was able to see it for the first time in four decades, and his commentary, posted here, will give you a taste of how entertaining an e-mail buddy he could be. I wish we’d met in person; we came close, last year, but it didn’t work out. I am very sad that I won’t see more of those messages in my inbox.

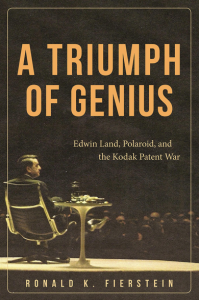

More than a year ago here, I mentioned a history of Polaroid by Ronald K. Fierstein that was in the works. A Triumph of Genius: Edwin Land, Polaroid, and the Kodak Patent War has arrived in bookstores, and I am very, very happy to see it there. Ron was one of the lawyers on Polaroid v. Kodak, spending a lot of time with Edwin Land himself, and the book exudes the authority gained from years of deep research and immersive life experience.

More than a year ago here, I mentioned a history of Polaroid by Ronald K. Fierstein that was in the works. A Triumph of Genius: Edwin Land, Polaroid, and the Kodak Patent War has arrived in bookstores, and I am very, very happy to see it there. Ron was one of the lawyers on Polaroid v. Kodak, spending a lot of time with Edwin Land himself, and the book exudes the authority gained from years of deep research and immersive life experience.

As I have often said, my book may have been the first one to tell the complete story of Polaroid instant photography, but it’s hardly the end of the line: It was intended as an overview for a general audience. Since the company’s archives are now accessible to the public, further researchers will be digging into them and coming up with more detail and bigger books for years to come. This is the first, and (I venture to say) nobody will ever do the legal story better or more authoritatively than Ron has.

There’s a nice teaser in a recent issue of the Boston Globe’s Sunday magazine here, and an interview with the author on NPR’s “Marketplace” plus a little excerpt here. The book itself can be ordered from Amazon here—but hey, how about ordering from an indie instead? Here’s a Powell’s Books link.

LEGALITIES

This site is not connected with or endorsed by Polaroid or PLR IP Holdings, owners of the Polaroid trademark.ON TWITTER

My TweetsBlogroll

- 'Insisting on the Impossible'

- Everything Reminds Me of You

- Flickr's Polaroid group

- Instant Options

- LandCameras.com

- Paul Giambarba: Analog Photography At Its Best

- Paul Giambarba: The Branding of Polaroid

- Polaroid

- Polaroid SF

- Rare Medium

- The Impossible Project

- The Land List

- The New55 Project

- Vintage Instant