It wasn’t all that uncommon, back in the heyday of instant photography, for people to shoot Polaroid photos of celebrities or star athletes as a medium for autographs. It’s a cute and nonthreatening idea: You get to chat with the star for a minute while the photo comes out, and you get a nice souvenir of the moment. The white tab at the bottom of the Polaroid picture is just about the right size for a signature, too.

What I didn’t know about till recently, however, was the unnervingly large collection of these photos at Portroids. It’s all the work of one unnamed guy—still at it!—who presumably hangs around stage doors and autograph rope lines, and has been doing so for eight years. He doesn’t seem to catch that many of the hugest celebrities, but he has a few, like Robert Redford, and once you get down to the fame level of, say, Saturday Night Live cast member, he’s absolutely comprehensive. (In fact, he seems to have a particular taste for smart comedy people, like guys from The Daily Show.) He posts one a day on Twitter, and archives every one on his site.

Passing on a plea from a researcher at Vassar College named Mary-Kay Lombino, who is assembling a Polaroid photography exhibit to open in the spring of 2013. She is looking for a copy of Polaroid’s 1972 annual report, each copy of which had an original SX-70 print (a photo of a red rose) mounted on the cover. The copies at Harvard’s Baker Library are all missing their photos, and she wants to include one in the exhibition. Anyone who has a copy and would be willing to lend it, let me know and I’ll hook you up with her.

Bill Warriner—filmmaker and photographer who spent a lot of years in Polaroid’s marketing department—e-mailed the other day to remark on the company’s original logo. This is the one that’s an abstraction of a pair of crossed polarizing filters, here seen on the corporate letterhead:

It’s the symbol that Paul Giambarba and then Bill Field moved away from, in favor of the News Gothic logo that started appearing around 1958. “Soap bubbles” is how Giambarba described the old one, and when rendered on a pale background, that is how it sometimes looked.

Anyway, Bill Warriner told me something I did not know: Within the company, the logo was nicknamed “the Crosseyed Owl.” And, he added, when it came time to build a small café in Polaroid’s offices at Technology Square, Bill Field and his colleagues decided to have a little fun. The café was itself named the Crosseyed Owl, and its walls were papered with images of those very birds (some crosseyed, some not).

Well, as soon as he said it, I was finally able to understand this photo, which I had in my files:

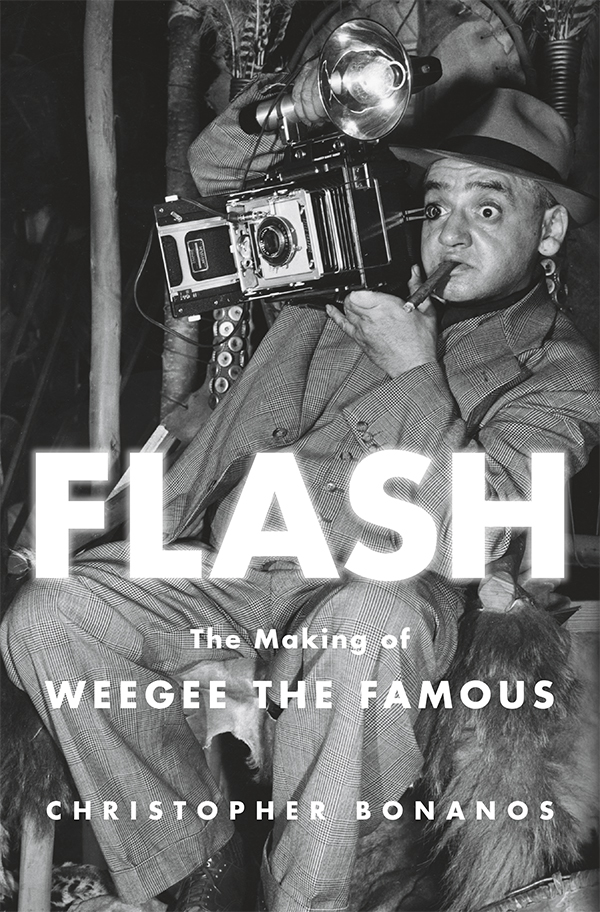

Got a few photos from our BookExpo America signing, shot by P.A.P.’s Russell Fernandez while I was snapping and scribbling. (Plus one extra photo, via Twitter, from the book blogger known as The Picky Girl.)

The earliest Polaroid cameras were, as Edwin Land once said, “grand machines for a grand purpose.” The original Model 95 weighed more than four pounds, mostly of brass and steel. (I suspect that the reason you still see a lot of them at yard sales and on eBay is that people don’t like to throw away anything so substantial.) Their robustness made them durable, but it came at a cost to Polaroid’s business: Nearly all the early buyers were men, because the thing was so damn big that a lot of women simply didn’t want to lug it around. Polaroid’s marketing people knew, too, that a lot of household snapshots were taken by moms.

To appeal to them, in 1954 Polaroid introduced a smaller camera called the Model 80. Here’s what it looks like:

It was also marketed as the “Highlander,” with a logo carpeted in plaid.  Judging by other cultural artifacts I’ve seen, this kind of name was often applied to products that were budget-priced. “Highlander” conveyed “Scotsman,” and “Scotsman” conveyed “thrift.” I vaguely remember Plaid Stamps, a discount system comparable to S&H Green Stamps, that carried the same connotation during my childhood. (Ethnic shorthand like this, common at the time, has—ahem—fallen out of favor. People are scunnered, as a Scotsman might say.)

Judging by other cultural artifacts I’ve seen, this kind of name was often applied to products that were budget-priced. “Highlander” conveyed “Scotsman,” and “Scotsman” conveyed “thrift.” I vaguely remember Plaid Stamps, a discount system comparable to S&H Green Stamps, that carried the same connotation during my childhood. (Ethnic shorthand like this, common at the time, has—ahem—fallen out of favor. People are scunnered, as a Scotsman might say.)

Here’s how the camera looks next to its overbearing husband:

The difference appears modest, but when you pick the two up, it’s obvious that the Highlander is much lighter, and it’s a lot easier to wield, especially when you’re holding it up to your eye. It made correspondingly smaller photos, too–2 1/2 by 3 1/4 inches, instead of 3 1/4 by 4 1/4. The film produced under the name Type 42 for the big cameras was called Type 32 in the smaller format, and Type 47 corresponded to Type 37. (Much more about Polaroid roll films here, at the Land List.) Otherwise, though, it worked the same way. The photos processed themselves inside the camera, and were removed through a door on the back after they developed.

The difference appears modest, but when you pick the two up, it’s obvious that the Highlander is much lighter, and it’s a lot easier to wield, especially when you’re holding it up to your eye. It made correspondingly smaller photos, too–2 1/2 by 3 1/4 inches, instead of 3 1/4 by 4 1/4. The film produced under the name Type 42 for the big cameras was called Type 32 in the smaller format, and Type 47 corresponded to Type 37. (Much more about Polaroid roll films here, at the Land List.) Otherwise, though, it worked the same way. The photos processed themselves inside the camera, and were removed through a door on the back after they developed.

The Model 80 was a success, and stayed in production until 1961. Along the way it got a couple of tweaks, so later examples are marked 80A and 80B. This one is a Model 80A that belonged to Eelco Wolf, a longtime Polaroid marketing and corporate-communications executive. He gave it to me when I visited him recently–he said he was happy to have one more bit of clutter out of his house, and I was just as happy to acquire it.

And since I can’t resist adding to my own clutter, I recently found a matching accessory on eBay. Model 381 Shoulder Case, still in its box, never used. Nice heavy cowhide, burgundy corduroy interior, little elastic loop on the inside of the flap to hold your tube of print coater.

I’d love to try the camera out, but the 30-series films went out of production around 1980 or so, and any film that’s still around is almost surely dry and dead. (If I ever find some in a fridge somewhere, I’ll try it out. Unlikely to happen, even less likely to work.)

The case, however, will finally get out of its box and see some use. It turns out to be exactly the right size to hold a folding SX-70 camera and a pack of Impossible film, and the elastic doohickey will nicely hold the flash that Impossible and Mint have recently started selling. The only thing missing from this Shoulder Case, curiously enough, is the actual shoulder strap–it has a short handle, one you can’t slip your arm through. Someone must’ve swiped it long ago.

LEGALITIES

This site is not connected with or endorsed by Polaroid or PLR IP Holdings, owners of the Polaroid trademark.ON TWITTER

My TweetsBlogroll

- 'Insisting on the Impossible'

- Everything Reminds Me of You

- Flickr's Polaroid group

- Instant Options

- LandCameras.com

- Paul Giambarba: Analog Photography At Its Best

- Paul Giambarba: The Branding of Polaroid

- Polaroid

- Polaroid SF

- Rare Medium

- The Impossible Project

- The Land List

- The New55 Project

- Vintage Instant

Magnificent Results From You Too, Guys

This has nothing to do with Polaroid especially, and it will be old news to those of you who have your own blogs. It is, however, an interesting discovery I’ve made since Polaroidland opened for business at the beginning of this year: the sheer number of robot-generated spam comments that get posted to this site every day. (I dispose of them before they appear on the site.) At least some of them are wonderful in the way that only Google Translate can make them. (Especially the weird anti-compliments: “You actually understand what you’re speaking approximately!“) A little found poetry, assembled from a list I’ve been keeping:

Unquestionably believe that that you simply said.

The article has really highs my attention.

Remarkable issues here. I’m very glad to peer your post.

Share we keep up a correspondence more approximately your article on AOL?

You managed to hit your nail after the top and also defined the whole thing with no side effect, men and women could take a signal.

You available my mind, and that I definitely agree with you.

Magnificent goods from you, guy.