Exciting, long-awaited news: Grant Hamilton’s new Polaroid-and-Impossible documentary is getting its first big public screening. Time Zero will be publicly shown on April 28, in Somerville, Massachusetts, as part of the Independent Film Festival Boston. (It’s at the Somerville Theatre at 1 p.m., if you’re ready to jump in your car.) It has its own Twitter feed, here. And to hold you till then, here’s the trailer.

Honest to god, I teared up a little when watching it. I really did.

Eastman Kodak posted this item from the archives a couple of years ago, but I hadn’t discovered it till now. It’s a test of Kodachrome movie film, from 1922. Color movies, in near-perfect condition, made four years after the end of the First World War. Though it’s not the earliest color movie film in the world, it’s way older than most. (The first Technicolor feature, Becky Sharp, wasn’t released till 1935.)

There are four women in the film, plus one little girl. According to a post on Kodak’s site, two of the women are the silent-film stars Mae Murray and Hope Hampton, and you can tell: They occupy their time on camera with those coquettish flapper moves that silent-era actresses specialized in: the coyly twisted shoulder, the eye-roll and moue. It is very strange, though, to see those conventions in color. We have internalized the black-and-white-ness of that world, and it separates us from them—twenties figures in black-and-white seem to be from another planet. Add color into the equation, though, and the women look like people you’d see at a restaurant in my neighborhood—barely antique at all. Only the hats give them away, and even those are not so outlandish. (The soundtrack helps, too. Nice job, whoever added it.)

The person I can’t stop wondering about, though, is the little girl who’s on camera for just a few seconds. She’s perhaps 5 years old in the film, meaning that she was born around 1917, and may well have made it into the 2000s. She’d be 95 now. Could she possibly still be out there somewhere?

Because of its size, the 20×24 Polaroid camera tends to do mostly studio work. There are exceptions—Jennifer Trausch has taken it out in the field now and then, as have others—but those shoots are comparatively rare.

And then there’s the work of Joachim Knill, a Swiss-born photographer who built his own field camera to shoot Polaroid’s 20-inch-wide spools of film. It looks like an absolute contraption, with a lumpy bellows and spidery legs, and its frame is a little taller than those of the Polaroid-built models—his pictures are 20 by 30 inches. But never mind what it looks like: It’s the photos this camera makes that will stop you in your tracks.

Knill eschews the fairly cool aesthetic that is in vogue now in favor of an over-the-top maximalism. His frames are crammed with stuff, with color, with light. He favors translucent stuff that (I’m guessing) he lights with colored gels, producing results that look like dioramas produced on another planet. The aesthetic that leaps to mind is that of Terry Gilliam, but even that doesn’t quite get you there. He’s marching to no drummer except the one in his head.

He operates mostly away from the New York gallery system, judging by his Web schedule, which lists mostly art shows and fairs in places like Oklahoma City and Tampa. Someone: Sign this man up and give him a big show!

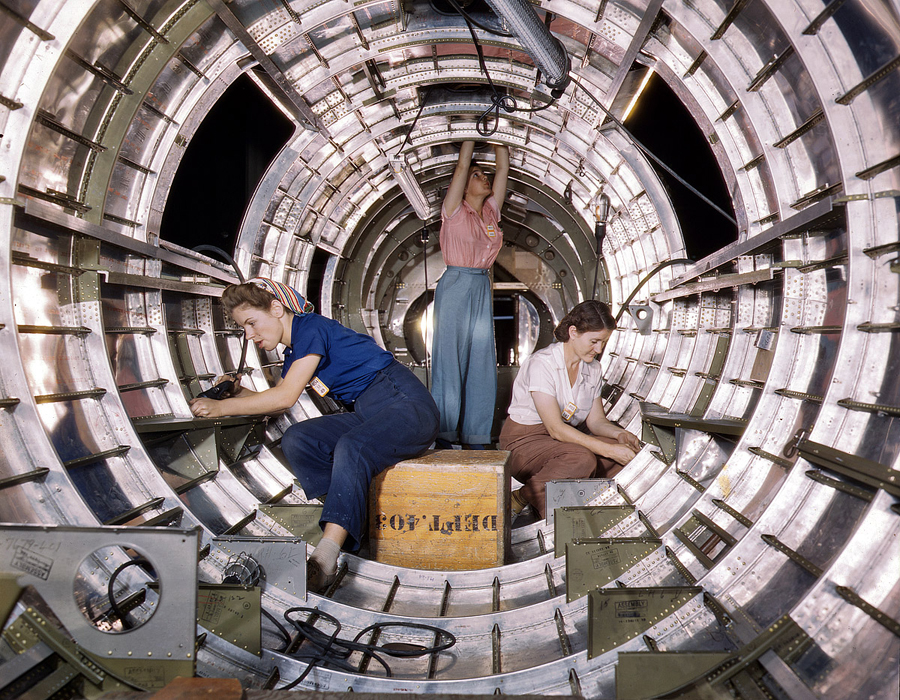

A group of semi-anonymous photographers, shooting 4×5 chromes for the Office of War Information, made some of the most incredible portraits of ordinary Americans that I’ve ever seen. One in particular, named Alfred Palmer, deserves his own mini-retrospective. Click for full-size images; they have to be seen big to be appreciated.

October 1942. Workers installing fixtures and assemblies in the tail section of a B-17F bomber at the Douglas Aircraft Company plant in Long Beach, California. 4x5 Kodachrome transparency by Alfred Palmer.

Most are images of men and women at work on the war effort—Rosie the Riveter gals, men operating heavy machinery, servicemen and -women. There are (according to the Library of Congress, which has the collection) 164,000 in black-and-white and 1,600 in color.

October 1942. "Noontime rest for an assembly worker at the Long Beach, Calif., plant of Douglas Aircraft Company. Nacelle parts for a heavy bomber form the background." 4x5 Kodachrome transparency by Alfred Palmer.

October 1942. "Lieutenant 'Mike' Hunter, Army test pilot assigned to Douglas Aircraft Company, Long Beach, California." 4x5 Kodachrome transparency by Alfred Palmer for the Office of War Information.

October 1942. Engine installers at Douglas Aircraft in Long Beach, California. 4x5 Kodachrome transparency by Alfred Palmer.

Is that her hipster Williamsburg boyfriend?

Quite a few of them were shot with some kind of foreground illumination, meaning that the backgrounds fall into nearly solid black, giving these the quality of dramatic set-pieces, but as far as I know they’re all documentary.

Access to the full collection here; Shorpy page here; a nice selection, assembled and presented by a Russian fan, here.

Self-explanatory slideshow on British Vogue’s Website here, by the casting director Douglas Perret. These are a few years old, and several of the models have since added “super-” to their job descriptions. (He’s publishing a book of these photos called Wild Things.) Looks like Spectra film rather than Instax.

We’ve already discussed the gold Polaroid camera … how about silver?

Ben High is an L.A. photographer and Pola-fan who, not long ago, moved to Iowa and set up shop as a jewelry-maker. As his Website says, “The first super fun thing I’ve been working on is, of course, related to photography. I built this Polaroid SX-70 in sterling silver.”

Often when you see little charms of made to mimic familiar objects like this, they have a slightly slumped and distorted quality to them. This one, by contrast, is precise, with clean sharp corners and a very high level of attention to detail. (The proportions of the ring around the electronic eye are exactly right, as are the creases in the bellows. And you can tell that it’s the original model rather than the Alpha, because he’s left off the strap lugs.) He charges $75, which frankly does not sound like very much for this level of craft. Site is here; his e-mail address, rendered to foil the spambots, is benjaminhigh [–AT–] gmail [–DOT–] com.

LEGALITIES

This site is not connected with or endorsed by Polaroid or PLR IP Holdings, owners of the Polaroid trademark.ON TWITTER

My TweetsBlogroll

- 'Insisting on the Impossible'

- Everything Reminds Me of You

- Flickr's Polaroid group

- Instant Options

- LandCameras.com

- Paul Giambarba: Analog Photography At Its Best

- Paul Giambarba: The Branding of Polaroid

- Polaroid

- Polaroid SF

- Rare Medium

- The Impossible Project

- The Land List

- The New55 Project

- Vintage Instant