Last week, my New York magazine colleague Ben Wallace did a bangup job writing about TED—the series of conferences devoted to “technology, entertainment, and design” at which very smart people touch antennae with other very smart people. The story extensively quotes Richard Saul Wurman, TED’s founder, who made his money publishing a series of travel guides under the rubric “Access”: Access New York, Access San Francisco, and so forth. Well, they weren’t all travel guides: A few were single-topic subjects (dogs, baseball), and at least one was a corporate project, about the history of a certain instant-photography concern.

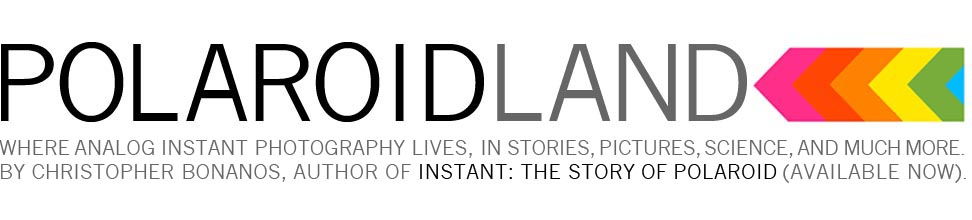

Polaroid Access: Fifty Years was published in 1987, to mark the company’s first half-century. It’s really nicely art-directed and produced, and I recognize lots of photos and other bits and pieces of material from the Polaroid archives. (I must say that it was useful, as I put my own book together, to have a predigested timeline indicating every milestone.)

It’s a nice synergy, Polaroid and TED. (And words like “synergy” are the essence of TED.) Edwin Land’s company was, especially before the 1980s, as much think tank as corporate entity, built around pumping out profitable ideas based on pure research. Only in its later years did it become principally a manufacturing concern, devoted almost solely to making cameras and film, and that’s when the problems began.

Copies are scarce, but they turn up in the $50 range now and then. There was a downloadable PDF online somewhere—I saw it a couple of years ago—but it seems to have disappeared. If it resurfaces, I’ll add a link. [Updated, 3/17/2015: Here it is!]

The Gallery 13 is one of a number of small green shoots that’s popped up in Asbury Park, New Jersey, in the past few years. (Asbury is one of those towns that spent the eighties and nineties fighting severe problems with drugs, crime, and blight, and appears to have turned the corner lately.) Its latest exhibition, “LoFi,” showcases pictures made with ostensibly junky plastic-lens cameras. It’s an aesthetic that matches perfectly the run-down-shore-town quality of Asbury, and I’m especially happy about it because my pal Jodi Shapiro will have a bunch of her stuff on view. (I also like the old-style peel-apart-Polaroid border on the poster, which suggests a level of instant-photo-literacy at work here.) If you’re anywhere near the Jersey shore, drop in for the opening on Saturday night.

The Gallery 13 is one of a number of small green shoots that’s popped up in Asbury Park, New Jersey, in the past few years. (Asbury is one of those towns that spent the eighties and nineties fighting severe problems with drugs, crime, and blight, and appears to have turned the corner lately.) Its latest exhibition, “LoFi,” showcases pictures made with ostensibly junky plastic-lens cameras. It’s an aesthetic that matches perfectly the run-down-shore-town quality of Asbury, and I’m especially happy about it because my pal Jodi Shapiro will have a bunch of her stuff on view. (I also like the old-style peel-apart-Polaroid border on the poster, which suggests a level of instant-photo-literacy at work here.) If you’re anywhere near the Jersey shore, drop in for the opening on Saturday night.

A special treat at the opening of “Momentum,” the Impossible Project’s latest exhibit, this past evening: I finally met Dr. Florian Kaps, the man who (with his business partner, André Bosman) saved Polaroid’s last instant-film factory from the scrapyard. We had spoken via Skype but never in the flesh. Tonight, we chatted, we joked, we traded Polaroid lore; he gave me a peek at a future product that looks extremely promising. Here’s the man himself. (It’s probably bad form to admit that I shot him on Fuji film, but at least it’s not Instax.)

I also was excited to meet Jessica Reinhardt, whose Polaroid photography I’ve been admiring online for quite awhile. Here she is with Patrick Tobin, who works in marketing and online sales for Impossible and is a really good photographer himself. (Soft focus, I know, I know; group shots are tough with the portrait lens on my Model 180, because DOF is about six inches and someone’s always too far back or too close in.)

Sam Yanes, the longtime corporate-communications chief at Polaroid, reminded me yesterday that Christopher Plummer—who on Sunday finally got his Oscar, becoming the oldest actor ever to win one—did Polaroid commercials. Here he is, in 1980, teasing the Sonar SX-70:

This polished 30-second spot is somewhat similar to the introductory SX-70 ad that Laurence Olivier made in 1972, which broke the great-actors-don’t-do-commercials taboo.

I know from my research that Olivier’s agent, after his first year’s worth of ads, got wise to his client’s worth and begin progressively raising his rates. So I have to wonder: Did Plummer get the call after Olivier got too expensive?

I kinda figured that Outkast’s “Hey Ya” (you know, “shake it like a Polaroid picture”) would be the swan song for Pola-pop. I wasn’t even close, though. A few weeks ago I posted about Allo Darlin’s “The Polaroid Song,” and not one but two more videos have lately celebrated everyone’s favorite snapshot medium. Both songs, by odd coincidence, are just called “Polaroid.”

One’s by a mononymic singer named Vali, freshly signed to Rostrum Records (home to the hip-hop star Wiz Khalifa). She spends part of the video wielding a pink-and-gray 600-series camera, probably from the early 1990s, that just may be older than she is.

The other is much poppier and more whimsical, and is by Skyler Stonestreet. She’s one of those artists who’s become adept at working around the collapsed hulk of the music industry, gaining some national traction on her own (mostly via social networking) without a record label. She bats her eyelashes a lot.

Stonestreet’s video is built around one of the new Grey Label cameras from the current Polaroid, which do not use traditional film, and the little white-bordered photos it produces are all over this clip. Between that and the slickness of the video, I am guessing (based entirely on circumstantial evidence) that she got a little money from Polaroid toward the filming. I don’t begrudge her a bit: If Old Polaroid gave tons of film and cameras to artists and kids, no reason New Polaroid shouldn’t be in the same game. Besides, how can you argue with a cheery pop song?

In my research for this book, I’ve discovered that, if you look hard enough, almost anything eventually connects to Polaroid. Even Britney Spears.

The i-Zone was the last hit product introduced by the pre-bankruptcy Polaroid. It appeared in 1999, and made tiny integral-film photos, the size of a 35-mm. negative—that is, an inch by an inch and a half. The camera was small, too, about the size and shape of a toothpaste box. Some versions of the film were made as peelable stickers. They were a huge hit among teenagers and even younger kids, and for a little while, you’d see i-Zone photos on every looseleaf notebook in every junior high in America. (The darker part of the story is that the film, unlike everything Polaroid made during its golden age, was produced by cheap Mexican labor; I’ve heard, but cannot confirm, the grim story that those tiny film packs were not only consumed by children but also made by them.) Britney Spears—who, you may remember, was a Disney star back then, one who was promoted as an utterly wholesome creature of family values—did the ads. Love the tagline: “The real Britney. In five photos or less.” Maybe not quite, judging by what we learned a few years later. (And let us not discuss her generally fraught relationship with photography, at least the paparazzi kind.)

Teenagers being teenagers, the craze burned itself out, and i-Zone did not last. (Film was discontinued in 2006.) The product’s celebrity spokes-teen, however, is spreading her weirdly compelling brand around Louisiana and Hollywood to this day.

LEGALITIES

This site is not connected with or endorsed by Polaroid or PLR IP Holdings, owners of the Polaroid trademark.ON TWITTER

My TweetsBlogroll

- 'Insisting on the Impossible'

- Everything Reminds Me of You

- Flickr's Polaroid group

- Instant Options

- LandCameras.com

- Paul Giambarba: Analog Photography At Its Best

- Paul Giambarba: The Branding of Polaroid

- Polaroid

- Polaroid SF

- Rare Medium

- The Impossible Project

- The Land List

- The New55 Project

- Vintage Instant