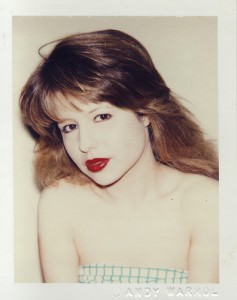

Andy Warhol was a compulsive Polaroid shooter, carrying a camera everywhere he went for many years. He was especially fond of a cheapo camera called the Big Shot, intended solely to make waist-up portraits from about four feet away. (You brought your subject into focus by making little half-steps toward and away from your subject, in a maneuver known as the Big Shot Shuffle.) Everyone’s framed the same way in a Big Shot photo. Yet when Andy shot them, he turned that constraint into a virtue. You focus on the face and pose (and occasionally the cleavage) rather than composition or any other qualities, since there’s not much else to see.

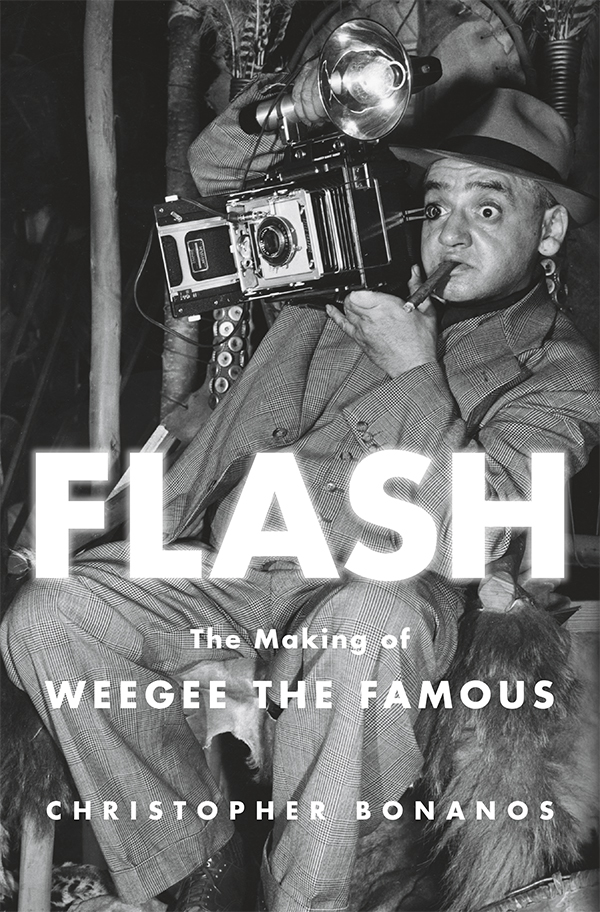

'Andy Warhol: Pia Zadora,' 1983; Polacolor ER; 4-1/4 x 3-3/8 in.; gift of the The Andy Warhol Center for the Visual Arts. © The Andy Warhol Center for the Visual Arts.

The University of California at Berkeley’s museum has a show of those Polaroid pictures on view right now, and it’s up through May 20. My millions of northern-California readers need to hop into their cars and get over there immediately. Slideshow at the Huffington Post will have to do the job if you, like me, are out of Prius range.

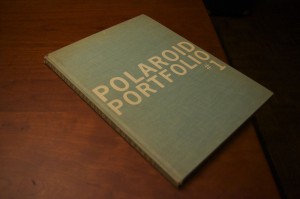

When you’re researching Polaroidiana, the names of certain people bob up around the edges over and over, and one of them is John Wolbarst. Wolbarst was the editor of a trade magazine, National Photo Dealer, in the late 1940s, and then moved on to become managing editor of Modern Photography in 1950. In that time, he saw the 1948 introduction of the Polaroid Land camera, and he was clearly one of the early guys to get the Pola-bug: He wrote about Polaroid steadily and enthusiastically, and in 1965 signed on as editorial director of its public-relations department. Before that, though, he’d already got involved with the company’s promotional efforts, putting together this volume, Polaroid Portfolio #1 (New York: Amphoto, 1959).

All it is, really, is a chapter of cleanly written and designed how-to, followed by about 110 pages of black-and-white photos, many at full-page size. The idea was to show off what Polaroid Land film could do, artistically speaking, and virtually every photo is captioned with technical details: whether it was shot on roll film or the larger sheet film, whether in a standard Land camera or a professional 4×5 system fitted with a Polaroid back, and so forth.

All it is, really, is a chapter of cleanly written and designed how-to, followed by about 110 pages of black-and-white photos, many at full-page size. The idea was to show off what Polaroid Land film could do, artistically speaking, and virtually every photo is captioned with technical details: whether it was shot on roll film or the larger sheet film, whether in a standard Land camera or a professional 4×5 system fitted with a Polaroid back, and so forth.

(It also contained this faintly comical errata sheet, whose instructions run almost as long as the correction does.)

The big photo of sailors and ship’s rigging on the right, explains the caption, was shot by Edmund Katz, Ph2, a Coast Guard cadet.

The glassware on the right is credited to Tosh Matsumoto, a fine mid-century photographer who, a brief online obituary reveals, died in 2010, aged 90. There are photos by many well-known artists in this volume, in fact–Ansel Adams, Philippe Halsman, Bert Stern.

Hands-down, the most entertaining bit of the book is this series of photos. They’re by a woman and are quite good, which seems to astonish Wolbarst, who (let’s be kind to him here) was no more enlightened than most men of his era. “Housewife’s Album,” these pages are titled, because the subjects are domestic (clothespins holding diapers on the line, neighbor kids come to visit). “Mrs. Paul T. Seamans is an attractive young Massachusetts housewife with four children,” it says, offering the textual equivalent of a pat on the head. “She is also an exceptionally able and imaginative amateur in the fine art of making pictures in a minute.” And then: “Her equipment is simple… With this, plus care, and an uncommonly perceptive eye, she has captured a record of her family, neighbors, friends, and their activies, of which anyone might well be proud.”

A later page reveals that she does, in fact, have a first name, which sent me off to Google, of course. I was delighted to find that the newlyweds reached their 60th anniversary. Mrs. Seamans along the way spent some years as a lab assistant at Polaroid, and not only did she keep taking photos; she got herself some serious art training, eventually built a following as a portrait painter, and got into sculpture as well. I would’ve liked to meet her , but I was (as with several people I wanted to interview for my book) just a little too late: Laurie Seamans died on March 23, 2011.

As for Wolbarst himself, he wrote another Polaroid-photography how-to volume, then joined the mothership full-time, staying at Polaroid until 1980, when he retired. He’s gone now, too: He died in Boston on November 12, 1986.

New to me (via Kat), and it’s pretty good! From a London band called Allo Darlin’:

You have to dig a lyricist who near-rhymes “stockpiling” and “expiring,” two words that loom large in film-photography circles these days.

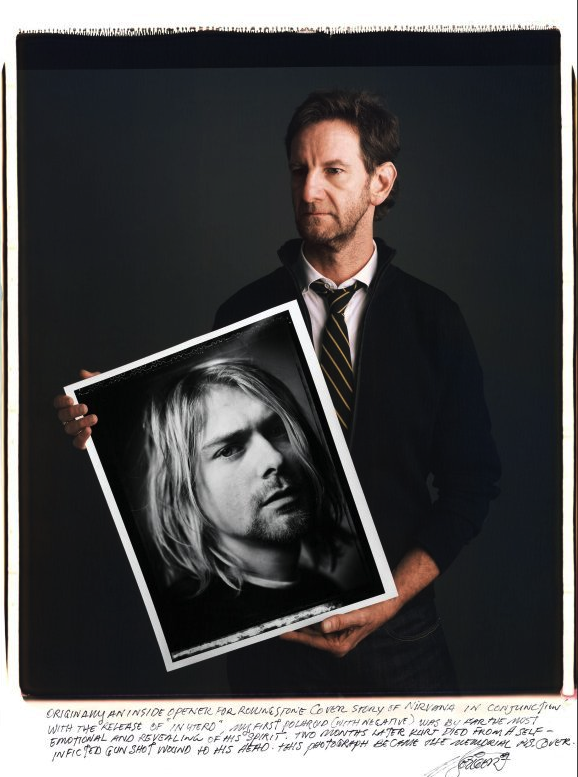

Tim Mantoani has spent the last few years turning the 20×24 instant camera inward on itself, making photographs of photographers. Each subject posed with a print of the image that, more than any other, defines his or her career. Once Mantoani got his big Polaroid shots, the subjects inscribed every one with a little story, anecdote, or history of how the original photograph came to be. Steve McCurry, who shot that legendary Afghan teenage girl for the cover of National Geographic, is here; so is Harry Benson, with an impossibly energetic black-and-white portrait of the young Beatles as they engaged in a hotel-room pillow fight.

Mantoani has just collected more than 200 of these in Behind Photographs, a big, impeccably produced volume that is available at three price points (basic, slipcased, and deluxe; frankly, even the basic one is far better made than most books). If you order through his Website, he’ll sign your copy. HuffPo has a slideshow from the book here.

Marc Seliger with his portrait of Kurt Cobain, by Tim Mantoani. The Cobain photo is also a Polaroid image, shot on Type 55 film two months before the singer took his own life.

What I like about this project is not just the VH1 Storytellers aspect, although that’s nice. No, what interests me is that many of his subjects are at the ends of their careers, looking back, and have been documented on a camera (and for that matter an entire medium) that until recently seemed to be itself living on borrowed time. These men and women spent their entire lives thinking about film: its grain, its speed, its tonal characteristics, whether the processing lab was open late on Saturdays. That’s not quite a lost art, but it certainly feels like horsemanship in the age of the automobile: something that, pretty soon, will be knowledge maintained by a self-selecting few. Mantoani used an extraordinary and endangered art material to document some of the finest practitioners of that art, and that, to me, is what makes this project something special.

Polaroid photography has has always had a cultish following. Something about the mystery of making a photo right away, yourself, adds an intimacy that makes certain people (like me) wildly enthusiastic about this medium. I, however, have not gone as far as the folks below, who have permanently etched Polaroid iconography into their skin.

Sometimes the image is straightforward…

..and sometimes philosophical.

Possibly my favorite belongs to Jessie Barber, a photographer and artist in Chicago, because it shows the same packfilm camera I use. Her tat (shown here in a self-portrait) is by a fellow named Scott Santee.

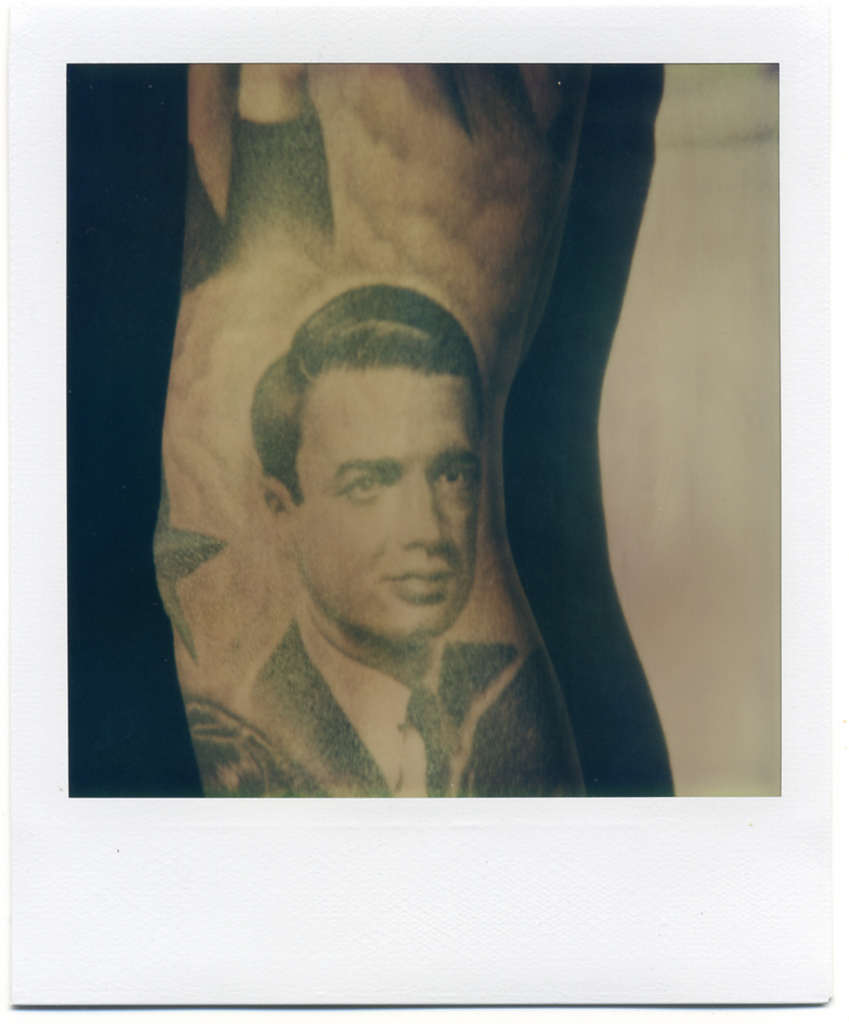

And finally there is this homage to Dr. Land, which really outclasses my ability to provide commentary.

Well, they weren’t all great products. This is the Polaroid JoyCam, produced in 1999.

In 1995, Polaroid got a new chairman, only its fourth in 60-odd years. His name was Gary DiCamillo, and he was the first outsider to run the company, having come in from Black & Decker. He arrived with an entirely different philosophy from his predecessors, calling for lots of fast product development rather than basic research—he said he wanted 20 to 40 new products a year to go out the door, to amp up the company’s metabolism, and it was a somewhat defensible position at the time, if a shortsighted one. Most of those products were not successful; the idea was to throw them all out there and see if anything took off. One of them, in fact, did–the tiny-format i-Zone camera for kids, and although it did not blow up quite big enough to keep Polaroid out of bankruptcy, it was a genuine hit. Then there was the JoyCam.

It’s probably the crummiest camera Polaroid ever made. It used Type 500 film—the small-size integral-film cartridge created for the failed Captiva camera of the early 1990s. Until this era, Polaroid hadn’t really got into exporting its jobs, apart from one camera plant in Scotland and some film factories overseas. This baby, though, was the advance guard in the march to make everything in China. I think it sold for about $20, and it had a flash, so I suppose you got what you paid for. It is lightweight, I’ll admit that.

Arguably the worst design aspect of this camera is the picture-ejection system, which involves pulling a ratcheted strip to pop the photo out, since there’s no motor. But that strip has a loop handle at the end, which you’d naturally grab to carry the camera, and if you were to tug on it too hard, you’d waste a picture. Ridiculous.

My favorite awful detail—pointed out by Marty Kuhn, over at the Land List—is that the hinge holding the back door onto the camera is not metal, not plastic, but a paper sheet: the instruction sticker on the back of the camera. Tear the paper, and the door falls off.

Put this next to anything else Polaroid produced—even the cheapest packfilm cameras of the seventies, or the humblest boxy OneStep descendants of the nineties—and it makes those look like Leicas. (Say what you will about the Swinger or the Super Shooter: They were well-finished and took decent pictures. They were inexpensive but never cheap.) The JoyCam looks more like the disposable packaging of a consumer product rather than the actual thing that package ought to contain.

The odd name “JoyCam” apparently first appeared in the Japanese market, possibly on a different model, and it does have that curious-to-English-speakers quality that many Japanese product names have. Why it was then used in the U.S., I have no idea. Why this was sold is slightly more evident—massive cost-cutting, plus the desire to get someone, anyone, to buy Type 500 film. Didn’t get anywhere; Type 500 went away a few years later, because a significantly smaller picture from a camera that was barely smaller than the standard 600 model was no bargain.

I own mine because of an odd project back in 1999 at New York magazine, where I work. We were doing an enormous survey of takeout restaurants in New York City, and an editor in each neighborhood was instructed to order in every night for a few weeks and rate all the meals. We were each given a JoyCam with which to document each delivery. Last gasp before digital (not to mention before SeamlessWeb, Yelp, and the rest of the online food business). I remember nothing about the project except that (a) most of the food was pretty bad, (b) everyone in the office was expecting to enjoy the freebies but turned very grouchy after a week of strictly dictated takeout meals, and (c) I did discover and recommend a good and inexpensive sushi place, which has since gone out of business. Power of the press, hah.

LEGALITIES

This site is not connected with or endorsed by Polaroid or PLR IP Holdings, owners of the Polaroid trademark.ON TWITTER

My TweetsBlogroll

- 'Insisting on the Impossible'

- Everything Reminds Me of You

- Flickr's Polaroid group

- Instant Options

- LandCameras.com

- Paul Giambarba: Analog Photography At Its Best

- Paul Giambarba: The Branding of Polaroid

- Polaroid

- Polaroid SF

- Rare Medium

- The Impossible Project

- The Land List

- The New55 Project

- Vintage Instant