I spent more than a year writing this book, and the most intense push was in January 2011. That’s when I spent two weeks in Boston, mostly at Harvard Business School’s Baker Library, where the Polaroid archives are kept. It was a tough trip: I was staying with my college roommate Mike and his wife, and although they could not have been nicer, two weeks is an awful lot to ask of anyone, and I was concerned about becoming the Guest Who Would Not Leave. (I went home weekends, and wrote rough drafts of three full chapters on the train.) On top of that, the Northeast was in the middle of a vicious, protracted cold snap, and HBS lies directly on the Charles River, whose wind was unbelievable. If Mike had not generously ferried me to and from the train station each day, I would’ve had to trudge through six-foot snowdrifts each morning and night, on dark streets without sidewalks. (The trip was supposed to be three weeks instead of two, but a blizzard closed down the roads and rails and kept me in New York for the first few days.)

That was a year ago this week, and it was 16 degrees Fahrenheit this Monday morning. Which all brings us to today’s Instant Artifact: the Polaroid Cold-Clip.

The chemical reaction by which instant pictures are processed depends heavily on temperature. When it’s 90 degrees out, Fuji’s FP-100C color film develops in one minute; at 50 degrees, it takes three times as long. When it’s really cold, it won’t work at all, which is where the Cold-Clip comes in. It is simply two sheets of aluminum—an excellent conductor of heat—that are hinged with a piece of tape. You keep it in your pocket, prewarming it. When you pull your photo from the camera, you tuck it inside the Cold-Clip, and, as the instructions say, “hold Cold-Clip between body and arm.” That’s right: Polaroid packfilm was, as far as I know, the first and only photographic product whose instructions involve shoving it into your armpit. Has to happen fast, too, so the process involves a frantic little dance.

Jokes about stinky-sweaty photos aside, this wasn’t (and isn’t) an ideal process. There’s always a little leakage of the reagant from a packfilm print, and after a day of outdoor shooting in cold weather, you can count on white streaks of dried chemicals all over your shirt. But it does work.

Two Cold-Clips pictured here, both from Automatic 100 cameras, each with (for some reason) different typography; the one on the left is a little nicer, if you ask me. There are other sizes, too, packaged with different cameras. Like so many things in life, the right-hand one in the photo fell apart with age and has been repaired with duct tape.

Instruction sheet below, front and back, if you really want to get into it. (Click to enlarge.)

Note that photographers still wore ties then, and did not worry about white streaks on their nicely pressed suit jackets.

You know the scenes, partway through Close Encounters of the Third Kind, where Richard Dreyfuss cannot stop seeing the Devil’s Tower shape wherever he goes? In his mashed potatoes, in his doodles, and eventually in the giant heap of dirt and rubbish that he constructs, maniacally, in his living room?

In the past year, the white Polaroid frame has been my Devil’s Tower: ever-present, as if it’s taking over my brain. It appeared before me in a shop window not long ago:

And just today, my colleague and friend Jillian pinged me, having discovered the Polaboy. It’s a giant lightbox, illuminated with LEDs and propped against the wall, and it looks like… well, here it is. I’d happily own one.

If you discover me hiking to the site of Dr. Land’s Osborn Street laboratory in Cambridge to make contact with the mothership, please tell my family it was something I had to do.

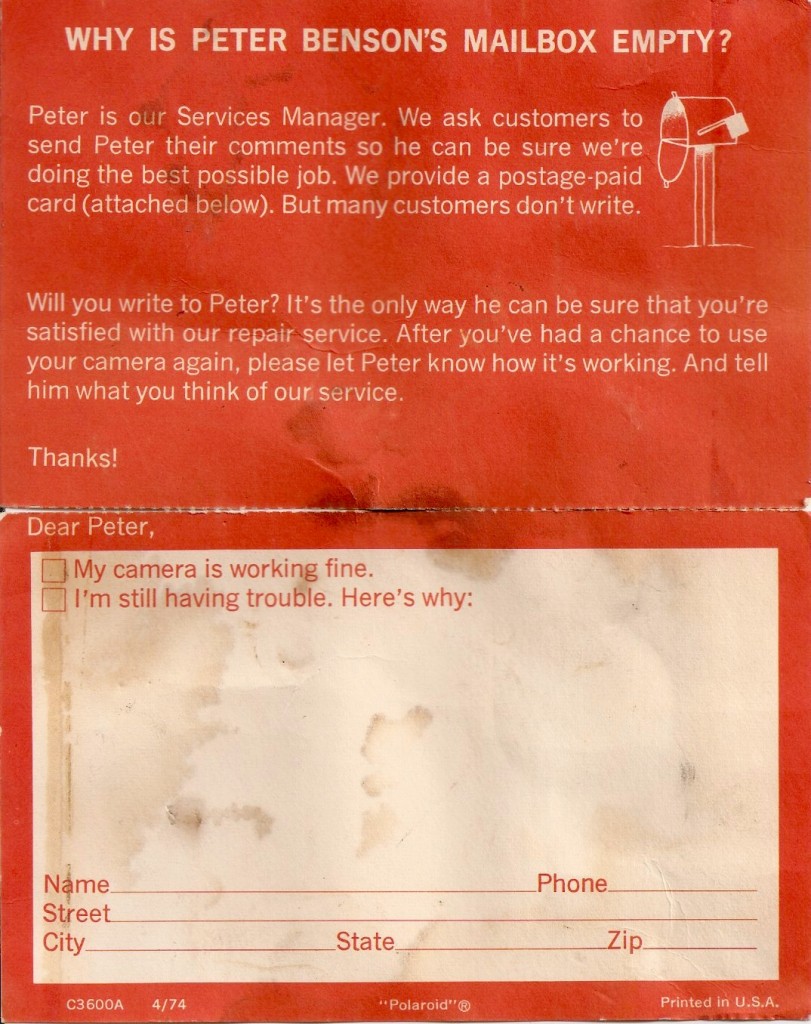

A whimsical, slightly odd item today. This is a reply card dated April 1974. It was tucked into the case of an old camera I bought.

A little goofy, to be sure, but it underscores two things about Polaroid that I have noticed over and over: (a) intelligence and sophistication in the marketing department, matching the brains on the technical side, and (b) a sense of the playfulness of instant photography. People goof around with instant cameras, experiment with them, try knocking off a photo or two when the odds of success are low. It’s a medium that encourages play, which is generally a good thing for art-making, picture-taking, and all-around creativity.

It’s tough to Google anyone with such a straight Anglo-Saxon name, and this evening’s searches reveal no trace of Peter Benson, Polaroid services manager. (The address on the other side of the card is in El Segundo, California, and I don’t see anyone in Boston or SoCal who fits the description.) Wherever he ended up, I hope he finally got some mail.

One site you’ll hear about regularly here is New55. It’s written by Bob Crowley, a fellow in the high-end-microphone business who is attempting to reproduce (with tweaks) one of Polaroid’s most astonishing products, the special 4×5 film known as Type 55.

Background first: Type 55 (and its offshoots, Type 105 and 665) were made principally for professional photographers, and they were the only instant films that produced both a print and a high-quality black-and-white negative. Type 55 was a favorite of Ansel Adams, who used it to make (among many others) El Capitan, Winter, Sunrise, Yosemite National Park, California, 1968. The prints are instantly (heh) recognizable by the markings left by a perforated paper sheet, known as a mask, around the edge of the photo. Here’s a great example. In fact, that border is so well-established that some people take the trouble to fake it, which seems extremely silly to me. It’s an artifact, people, even if it’s a pretty one.

You processed it much as you would any peel-apart Polaroid film—pull it through the rollers of a 4×5 camera back, wait, reveal—with one added step: a dunk in a sodium sulfite bath, after the fact, to “clear” and stabilize the negative. This could be done in regular room light, once you got home, so it wasn’t all that much of an imposition.

Type 55 was discontinued along with the rest of Polaroid’s film line in 2008, and a lot of photographers are still sad about that. Since then, Crowley’s made huge progress, and has even worked out one improvement on T55—the old film had mismatched ISO ratings for print and negative, so you had to choose between a correctly exposed print and a correctly exposed negative. His new product will be balanced, giving both in one shot. He has also replaced the sodium sulfite with ordinary black-and-white fixer, which is easier to find. An enthusiastic appreciation of the new film appears here.

According to Crowley’s New55 blog, if he can secure an investment of about $210,000, he can have production going in eight months. (Anyone reading this who’s feeling flush?) It won’t be cheap, at $6 per sheet, but honestly, 4×5 photography is never going to be a mass medium again, and when you factor in that you don’t need a darkroom to process this stuff, that isn’t really a bad price at all. Watch his page, and this one, for steady progress reports.

The Impossible Project’s film does not cope well with cold climates, so hats off to David Gilkey, who used it to document wintry life aboard the Trans-Siberian Railway. The premodern-looking sepia images are uncannily appropriate for this setting, evoking as it does an era when travel (like photography) was far more difficult than it is today. Slideshow here at npr.org.

Each week here, I’ll be posting photos of, and discussing, a Polaroid product from way-back-when. Many, but not all, will be coming from the deep recesses of a storage closet in my apartment. (Yes, I have a very tolerant wife.)

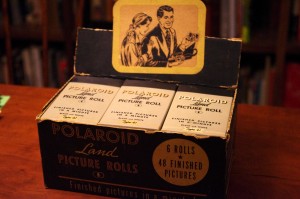

Today’s artifact is a fun one: A case of Polaroid roll film, unopened. “Use by December 1953.” Er, didn’t quite happen.

Type 41 was Polaroid’s original black-and-white film, introduced in 1950. (Its predecessor, Type 40, was the original Polaroid Land film, and made sepia photos.) Meroë Morse, a remarkable young Smith College graduate who worked for Edwin Land, was its midwife—Land himself being the one who birthed it. It was groundbreaking, and turning brown-and-white into black-and-white was (Land later said) among the toughest things Polaroid ever pulled off.

But it was not a perfect product. A few months after Type 41 was introduced, customers began to report that their photos were fading, and the chemists rushed back to the lab. A stopgap solution was cooked up by a colleague of Morse’s named Elkan Blout, and it was called film coater–a little tube containing a swab soaked in liquid plastic that was packed with every Picture Roll. Customers were instructed to lay each new photo flat and paint it with this nasty vinegary-smelling stuff. Though it was a mess, it worked pretty well, and may have saved Polaroid. It also inadvertently started a practice that we still see today.

Because those freshly coated photos were wet, people tended to wave them in the air to dry them off. In other words, this stuff created the Polaroid Shake. Never mind that later films were coaterless, or that today’s instant photos may actually be harmed by vigorous shaking. Most people shake anyway, and if you ask them why, you often get a baffled look: “I don’t know… it makes the photo develop faster?” (For the record, it doesn’t.) When Outkast’s Andre 3000 sang “Shake it like a Polaroid picture,” he probably did not realize that he was celebrating a ghost in the machine, going all the way back to 1950. But he was.

Side note: My wife noted that the guy on the box looks a bit like Edwin Land. I think she’s right, and I bet it’s not a coincidence.

LEGALITIES

This site is not connected with or endorsed by Polaroid or PLR IP Holdings, owners of the Polaroid trademark.ON TWITTER

My TweetsBlogroll

- 'Insisting on the Impossible'

- Everything Reminds Me of You

- Flickr's Polaroid group

- Instant Options

- LandCameras.com

- Paul Giambarba: Analog Photography At Its Best

- Paul Giambarba: The Branding of Polaroid

- Polaroid

- Polaroid SF

- Rare Medium

- The Impossible Project

- The Land List

- The New55 Project

- Vintage Instant